A Zen garden refers to the Japanese tradition of rock gardens, where a few simple and natural elements are combined to create a tranquil, stark and symbolic garden. The garden is comprised of two main elements: sand and rocks. Gravel is also used in place of sand. Natural elements such as grass and ornamental trees surrounding the garden may also be used.

The Zen garden consists of a pit of sand or gravel, with carefully placed islands of rock. The sand is artfully raked daily in patterns that evoke the ripples of the sea.

Japanese rock gardens got the western name, "Zen Garden," because of the tranquil nature of the garden, which encourage meditation and a Zen-like atmosphere. Zen, which is a school of Buddhism, is interpreted by many westerners to mean a state of introspection and enlightenment achieved by deep meditation.

There are several different types of Zen garden. The most famous is the dry garden, which is called "Karesansui." This word translates into “dry mountain and water garden.”

This type of Zen garden is designed in such a way that the raked gravel resembles water. To create the look of water flowing, small rocks, pebbles, and sand are used.

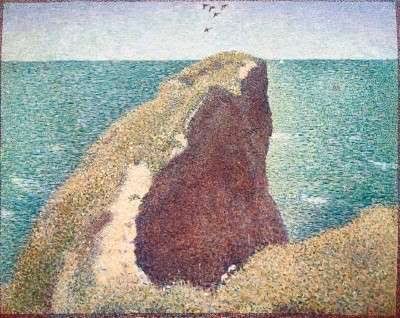

Often in the dry Zen garden, you will see one large rock that is the predominant feature. This rock is representative of the mountains that tower over the countryside. With this type of garden, it is believed that the stillness of the “water”, being the gravel, is the peace and tranquility of the mind.

Another type of Zen garden is one that is lush and green, and interestingly, would often be designed as a compliment to the dry Zen garden. This type of garden creates a magical illusion of a long journey found within a specific space. Many of the gardens have paths that meander through the garden, making their way around beautiful trees and shrubs as well as over streams and near waterfalls and statues. Each twist and turn of the path is designed to keep the individual’s mind on the spiritual journey.

The Zen garden has been a major part of history for centuries. Most of the early Zen gardens were quite large and provided the opportunity for Buddhist Priests to stroll throughout the garden. Then in the 11th Century, the dry landscape was adopted. It was then in the 13th Century that the principles of the Zen garden were finally established to what we know them to be today.

The purpose of the Zen garden is to provide a place of meditation and contemplation. When the Zen garden was first created by a Zen priest, it was actually called a Contemplation Garden. It was here in the United States that the term “Zen Garden” began.

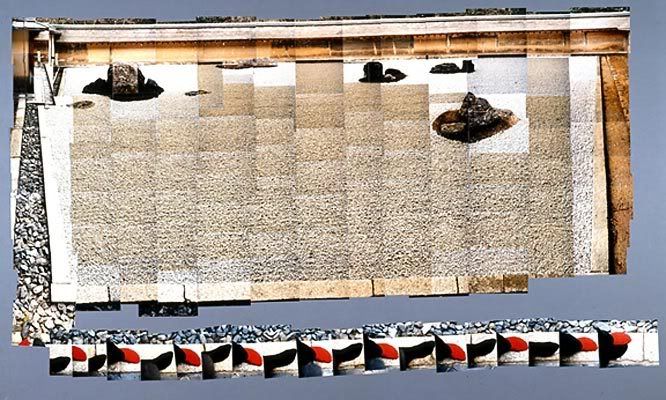

In late December 1995, my husband, our oldest child (who was 2 then) and I got to visit this famous Japanese Rock Garden in Kyoto, Japan. The Ryoan-ji Temple is the site of Japan's most famous and most austere rock garden.

RYOAN-JI TEMPLE

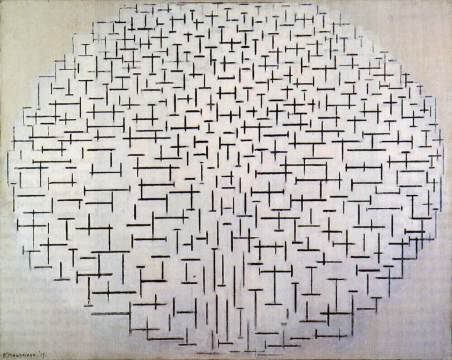

The Ryoan-ji Temple garden is considered to be one of the most notable examples of the "dry-landscape" style.

Some say the garden is the quintessence of Zen art and perhaps the single greatest masterpiece of Japanese culture. The space is surrounded by low walls. An austere arrangement of fifteen rocks sits on a bed of white gravel. That's it: no trees, no hills, no ponds and no trickling water. Nothing you could describe as romantic, distracting or pretty.

So what is it all about? Well, it certainly focuses the mind. Unlike Stonehenge, the Pyramids, or Angkor Wat, Ryoan-ji can hardly inspire you with technical achievement, religious imperative or sheer scale. But its minimalism inspires something else – contemplation, introspection, and deliberation.

The Ryōan-ji garden is famous for its simplicity. The longer you sit, the more the garden fascinates. The fifteen rocks are placed so that, when looking at the garden from any angle (other than from above), only fourteen of the boulders are visible at one time. It is traditionally said that only through attaining enlightenment would one be able to view the fifteenth boulder.

The Ryōan-ji garden is famous for its simplicity. The longer you sit, the more the garden fascinates. The fifteen rocks are placed so that, when looking at the garden from any angle (other than from above), only fourteen of the boulders are visible at one time. It is traditionally said that only through attaining enlightenment would one be able to view the fifteenth boulder.

Some believe that the garden represents the common theme of a tiger carrying cubs across a pond or of islands in a sea, while others claim that the garden represents an abstract concept like infinity.

Because the garden's meaning has not been made explicit, it is up to each viewer to find the meaning for him/herself. To make this easier, a visit in the early morning is recommended when crowds are usually smaller than later during the day.

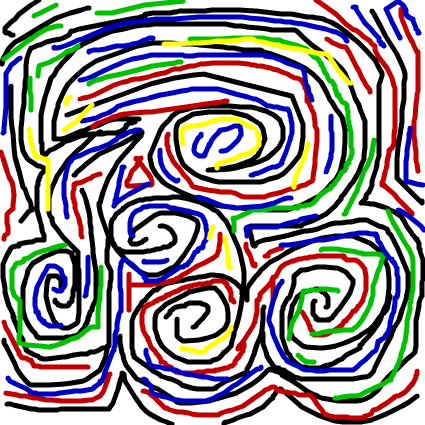

Here is a close-up of one of the rocks and the beautiful swirls of sand surrounding it.

No one knows who laid out this simple garden, or precisely when. Behind the simple temple that overlooks the rock garden is a stone washbasin. It bears a simple but profound four-character inscription: "I learn only to be contented".

Scholars continue to debate the the purpose of the garden and its significance. Many explanations are given for the rock arrangement and minimal decoration. Probably all that can be safely said is that the garden is highly influenced by the ideals of the tea ceremony, in which honesty, rusticity, and understatement are held in esteem. The ideals of wabi (honesty and understatement) resonated well with the Zen branch of Buddhism, leading to gardens like Ryōan-ji.

Wabi is a powerful design technique that uses simplicity and understatement to allow the viewer's imagination to "fill in the blanks." As one tourist asked a friend in Alan Booth's book, "Looking for the Lost: Journeys Through a Vanishing Japan " --

" --

"What's so special about the garden at Ryoanji?" I asked him ....

"What's so special about the garden at Ryoanji?" I asked him ....

"The spaces between the rocks," he replied, with his mouth full of toothpaste.

Probably more has been written about Ryōan-ji's fifteen rocks than all the other rocks in Japanese gardens combined. The raked sand does resemble water lapping at the base of mystical islands. Whatever its significance, the garden has inspired and continues to inspire designs to the present day.

Thousands visit the famous gardens

Creating the perfect Zen garden is now possible, thanks to the work of a team at Kyoto University in Japan. They used computer analysis to study one of the most famous Zen gardens in the world, at the Ryoanji Temple in Kyoto, to discover why it has a calming effect on the hundreds of thousands of visitors who come every year. The researchers found that the seemingly random collection of rocks and moss on this simple gravel rectangle formed the outline of a tree's branches.

The spacing of the rocks forms the outline of a tree's branches.

Viewed from the right position, this empty space created the image of a tree in the subconscious mind. The team from Kyoto University used image analysis to calculate the symmetry lines of the minimalist garden. They found that the points halfway between the rocks formed the outline of a tree's branches. The layout of the garden uses “suggestive symmetry” to make the brain visualize a tree by connecting the empty space between the rocks.

"We believe that the unconscious perception of this pattern contributes to the enigmatic appeal of the garden," said the team.

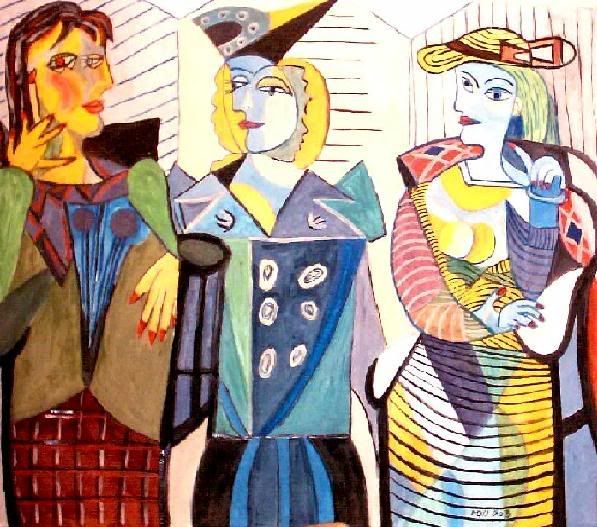

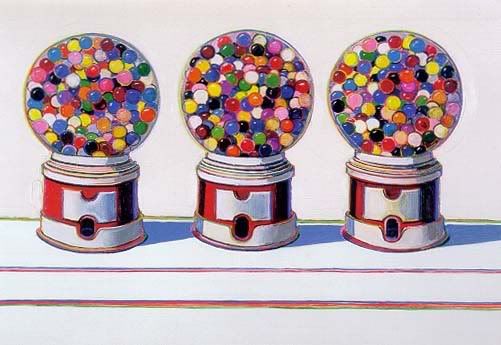

Here is British artist David Hockney's rendition of the Ryoan-ji Temple garden:

David Hockney (b. 1937). Walking In The Zen Garden At Ryoanji Temple, Kyoto, 1983

The nice thing about a Zen garden is that you do not need to have a huge piece of property to create one of your own. In fact, there are even Zen gardens so small they can fit on an office desk or coffee table. It is not about the size of the garden but the elements. Whether creating a Zen garden inside your home or outside, you will feel the peace and tranquility projected from this type of garden.